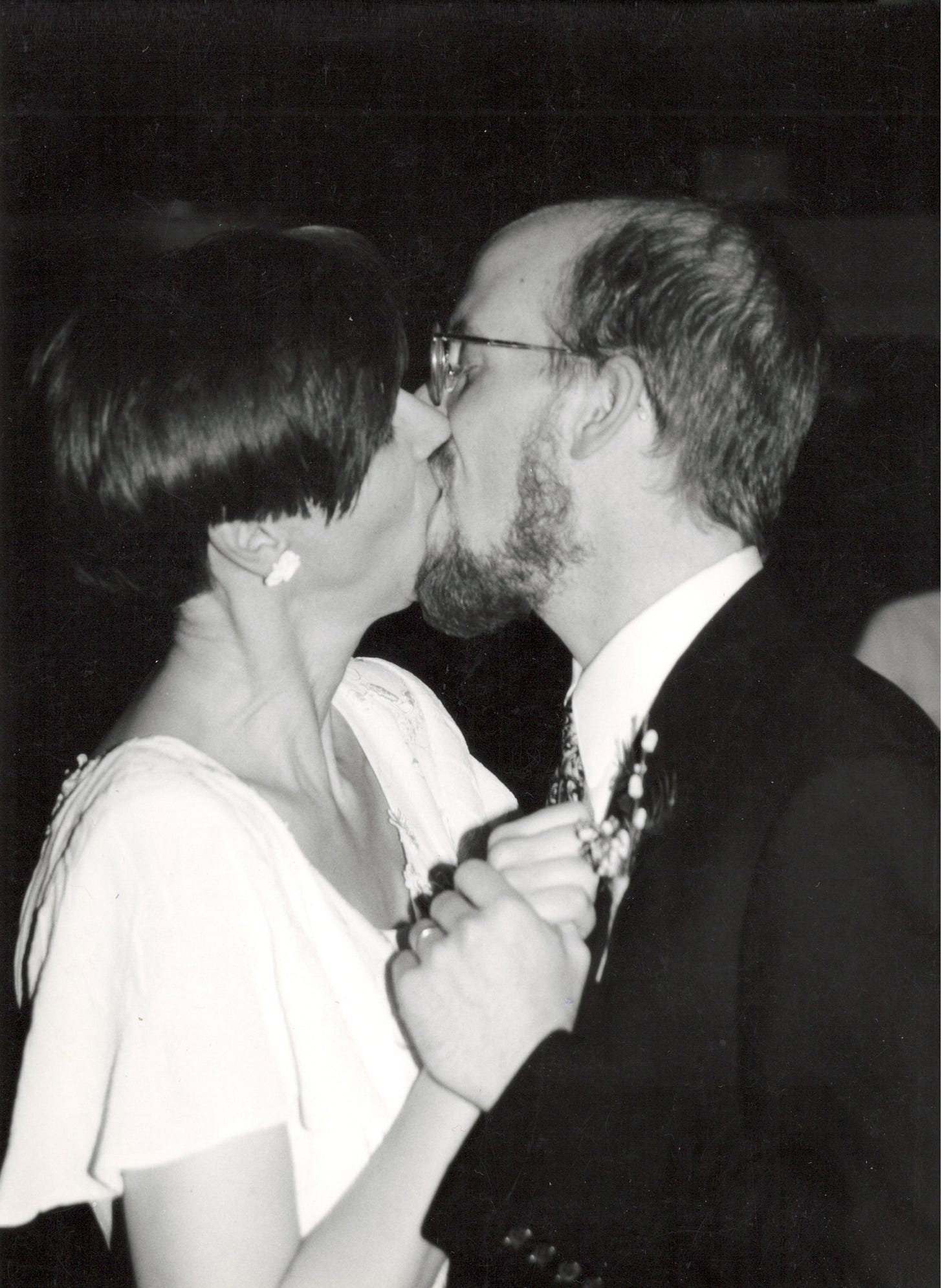

This is the kiss test

Plus: Caregiver coach Pat Snyder on being proactive and positive

Listen to me reading this story!

Now that I’m on my third issue, I suppose I should share a little bit about what Diane has and what “stage” we’re at with her disease. I didn’t want to do that right out of the gate because this newsletter is about cognitive caregiving, not illness.

Besides, the interesting thing about Diane isn’t what she has but who she is these days. When I’m in the room with her, I feel like she’s in some kind of liminal space where cognition isn’t required. She’s quiet but doesn’t seem bored. Sometimes she talks to visions I can’t see. Spiritually and emotionally, I sense that she’s all there.

And when friends or family drop in, I feel like the owner of Michigan J. Frog watching his pet burst into song. Visitors bring out a lively and talkative side to my bride. Diane’s former neighbor and work colleague, Sue Ellis, paid us a visit in November. Diane doesn’t remember working on textbooks in the ‘80s and ‘90s. But she was delighted Sue dropped by.

Anyway, to the medical business: Diane has Lewy body disease. It’s also known as Lewy body dementia and Dementia with Lewy Bodies. I’ll refer to it as LBD or Lewy. It’s been known to medical science almost as long as Alzheimer’s disease but has not been studied nearly as much.

Fun facts about Lewy:

It’s like having Parkinson’s and dementia. It’s two great diseases in one! It has to do with a certain type of protein deposit on the brain. Most people with Parkinson’s, if they live long enough, develop cognitive problems.

It’s probably the second most common form of dementia. I say “probably” because there are three different diseases all claiming to be the most common form of dementia after Alzheimer’s. Of the three, Lewy is the most complex, having fooled a lot of neurologists over the years. As diagnostic mastery of LBD spreads, the number of reported cases will go up. Already more than 1 million Americans are living with Lewy, compared with 5+ million with Alzheimer’s.

LBD was long misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s. Why does this matter? Because there are meds you can take that help slow the effects of Lewy and there are drugs to definitely avoid with Lewy. Also, think about what kind of torture it would be to have a loved one experiencing symptoms that didn’t line up with what the doctor was telling you. We’re fortunate that our neurologist did his residency at Mayo Clinic, an LBD Center of Excellence, and knew what to look for.

There’s no cure for Lewy. There are some promising signs, though, like tests that will detect Lewy biomarkers in a person before they’re symptomatic. I know one reader of The Diane Project who has benefited from this testing. The “survival rate” for most people after they are diagnosed with LBD is 5 to 7 years, though I personally know several folks who have lived much longer.

There’s also a not-so-fun fact involving the history of LBD and antisemitism, which you can read about in the Endnotes.

So that’s your Lewy 101. For many LBD caregivers, these medical facts are not that relevant. In my experience, neuroscience has little to offer the cognitive caregiver other than a diagnosis. Last week we had our first neurology appointment in 14 months, and we only did it to get one of her prescriptions renewed. At least we were able to have a “video visit,” a nice convenience even if it did remind me of the Terri Schiavo case.

More helpful are the monthly house visits from a nurse-practitioner who works for a local palliative care provider. She takes Diane’s vitals, asks if there have been any changes, any falls, that kind of thing. She’s focused on Diane’s well-being. Because her agency also handles hospice care, it’s a load off my mind knowing that someone with experience will be there when it’s time to transition.

Really, though, the only person who truly understands caring for someone with LBD day-to-day is another caregiver. As it happens, one of the very few in-person groups of Lewy caregivers in the Midwest meets once a month at a pie shop about three blocks from my house.

That’s right, I belong to both a soup club and a pie group. If anyone would like to invite me to their sandwich league or quiche society, you know where to find me.

The pie group formed out of a Chicago-based Zoom I joined shortly after the diagnosis. Made up of the wives of men with Lewy, plus me, our group brings several decades of combined caregiving to the table.

These ladies will be the first to point out that if you’ve met a person with LBD, you’ve met one person with that disease. Everyone in the group knows what a screwball disorder this is. No two cases are the same. Some people with Lewy are immobile while others go to the gym for Rock Steady Boxing. Some hallucinate happy creatures, others hallucinate monsters, while many don’t hallucinate at all. And every now and then you get the retired dutiful employee who slips out of bed at 4 a.m. and drives downtown because they’re late for a meeting.

Our experiences are different but our journey is the same and our community is like no other. Much of the essential guidance I’ve gotten has come from this group, listening to their stories and sharing mine. I remember when I was debating whether to hire my first aide and telling the ladies that I wasn’t sure I needed one. After all, I had spent years being around Diane 24/7. One of them sweetly smiled at me and said, “That’s because you’re in denial.” She wasn’t wrong.

***

The fourth anniversary of Diane’s diagnosis was last month, and I decided to look back to see how her disease had progressed. There are two widely-used dementia staging systems: FAST, a 1-to-7 scale based on common symptoms; and DSRS, a survey that scores the patient on 12 different categories including memory, social activity and personal care.

I used these systems two years ago and determined that Diane was in moderate to severe dementia. Today, according to both measurements … she’s right where she was two years ago. Which makes no sense. Even from my too-close perspective, she’s obviously undergone many changes since then.

So I called Pat Snyder, a former LBD caregiver who now coaches and teaches other caregivers. She spent the better part of a decade on the Lewy journey with her husband John, keeping him in such good trim that their neurologist, Dr. Daniel Kaufer, encouraged her to write a book. That resulted in Treasures in the Darkness: Extending the Early Stage of Lewy Body Dementia, Alzheimer's, and Parkinson's Disease, and a new vocation for Pat.

She leads a monthly caregiving class in Wake Forest, North Carolina, which she repeats on Zoom and YouTube. Her ability to explain LBD in plain language (e.g., this 13-minute video) is one reason Pat was named the 2019 Lewy Body Dementia Association volunteer of the year.

“You can't stage this disease,” Pat told me. “It's too much of a roller coaster. The experts that I respect the most, I hear them saying ‘early,’ ‘middle,’ ‘late.’ That’s about as good as you’re going to get with LBD.”

While Alzheimer’s is a predictable, mappable disease, Lewy symptoms come and go, fluctuating and baffling everyone around the patient. “You can have what looks like a very advanced disease one day,” Pat said. “The next day, all of the sudden people are asking, ‘Are you sure he has dementia?’“

What I love about Pat is her positive attitude and her belief that resilience and hope are muscles that can be developed. Above all, she helps caregivers to become more proactive, whether outfitting their bathrooms or coping with stress and grief.

I called Pat because of something she said during a presentation at the Dr. Daniel Kaufer Memorial Caregiver Conference in 2023. She says it during almost every talk she gives, and it was like a lamp I could carry into the cave of advancing LBD.

I screenshotted it from her slide deck so I wouldn’t forget:

I wanted to ask Pat about staging LBD and what might set apart late-stage Lewy from earlier stages. She began by telling me a story about her husband, and instead of the familiar roller-coaster analogy she used a different image, one that I found both helpful and deeply moving.

“In last couple of years of his life, John would go into this sleep where he would sleep for three days nonstop,” recalled Pat. “I had a syringe that I had used to feed the kids baby food, and I would syringe water to wake him up, and then to get some fluid into his body. That’s all he was taking in over a three-day period, maybe a little applesauce. And then he would bounce right back. The caregivers were like, ‘Oh, yeah, this is what happens at the end.’ But that went on for months and months.

“I got to the point where I just kind of floated with it. You just float. You’re in the stream, you’re floating down the stream, you don’t know what’s coming. And eventually — over time — you learn not to let that rattle you the way it did earlier.”

Wow, yes, exactly.

As John’s disease progressed, Pat developed a strategy that she now advises all her caregivers to try. She calls it “personifying the disease.” You separate the disease from your loved one, give it a name (Lewy is good) and treat it as your adversary, one that can be outsmarted and outmaneuvered.

“Whenever there’s what I call ugly behavior — paranoia, anger, suspicious or nasty behavior — just automatically say, ‘Oh, that's Lewy,’” Pat said. “If I saw that look on John’s face when I came in the room, I would go, ‘Forgot something! Be right back,’ and I would just get out of there. You don't feed the monster. You don't give the monster any attention at all. And when you get out of the room, he” — the loved one — “gets a reset.”

In the early years of her illness, if Diane got upset, confused or aggressive for seemingly no reason, I would push back. This never worked, since it hurt my wife’s feelings. Pat’s insight was to see her loved one as entirely blameless and Lewy as this troublemaker who has dropped by their house just to stir the shit. As a female caregiver dealing with a larger, more imposing man, Pat may have had a keener sense of her own helplessness that led to the creative approach of personifying Lewy.

It took me longer to get to that awareness. In the early post-diagnosis “stage,” I was under the illusion that Diane’s disease could be managed the same way we had managed previous health challenges. Then the Lewy body roller coaster started up. This “stage” felt like a nonstop parade of changes, which were not only stressful and unpredictable but had a habit of exposing my shortcomings. After a lifetime of relying on my wits, humor and occasional temper, I was confronted with an adversary that was immune to my cognitive charms.

It took time, but I was eventually able to develop a kind of jiu jitsu with Lewy. When it’s coming on strong, I need to give way. Meet aggression with tenderness. Pat’s image of this “stage” — floating downriver —is perfect. I’ve had to learn to accept what’s out of my control and to gently navigate the current as I wait for my loving spouse to float back into view.

“One of the things I love to say to caregivers, because I found it to be so true: If you’ve given this your best shot — and nobody does it perfectly, ever, ever, ever — but if you’ve given it a good shot, you’re going to like yourself better at the end of it,” Pat told me. “Because you will have learned something about love that you probably could not have learned in any other way. You’re going to be able to love more deeply and have much more compassion, because you had to. You just had to.”

A few weeks ago I made a delightful discovery while tucking Diane into bed. Our routine is the same every night. I brush and floss her teeth, give her a few pills and change her into pajamas. In bed I get her flat on her back and pull up the covers. Then I turn off the light, sit next to the bed and gently rub her head.

I don’t know the science behind this (and again, don’t really care), but the surface of the skull right above one of the most damaged parts of her brain is now the source of her greatest tactile pleasure. Many times she’ll go slack-jawed or fall asleep while I’m rubbing her temples. I keep this up until my arm gets tired, then I’ll lean in to give her a kiss.

One night I switched the order around, doing the head-rubbing and then turning off the light. Coming back to the bed, I leaned in very slowly, not yet able to see her face in the dark. As I got close to her lips, so close that I could feel her chin, I heard/felt her smooching the air.

I was struck by a flashback. Hundreds of mornings and evenings, Diane would throw me this same air kiss. Lying in bed, me leaning in, her eyes closed but sensing my nearness, her lips reaching out: smooch. It didn’t matter if we actually kissed. For 30 years this was our secret act of ordinary intimacy. I didn’t realize how much I missed it until that moment, when it popped out of the liminal space where cognition isn’t required.

The next day, I leaned in again, eager to repeat the magic. But she wasn’t having it. Undaunted, I tried again later, and that time I got a smooch. It was thrilling, almost like a first kiss. So I started doing it every day — the kiss test. She doesn’t know it’s a test, of course, but she’s not the one being tested, I am. And I have to earn it. I can’t just swoop down and get a smooch on demand. Like any lover, I have to get her in the mood, which is challenging when Lewy is in the room.

One evening after supper, I noticed her becoming preoccupied with a hallucination. She began talking past me to this vision across the room. I asked her what was going on, which was silly because she can’t explain things. So I let her go on a while, listening to the anxiety in her voice build. Finally I took her hands, looked her in the eye and said emphatically that I loved her and that I wasn’t going anywhere. It was just her and me in the room and we were safe.

That did it. She fell silent. I sat with her, grateful that my abracadabra had actually worked.

Later, as I tucked her into bed, I began my routine, rubbing her head and then, in response to her low hum of pleasure, moving down her body, making little sparks in the dark as I rubbed her chest and legs over the covers.

And lo, a spring of clear words suddenly flowed out. “It was a great day,” she said happily, “if you have the right attitude.” And then she smooched the air. Smooch smooch. Then she was out.

Endnotes

One of the great what-if’s of history is how much closer we might be to a cure for dementia today if not for antisemitism.

Lewy disease, like Alzheimer’s, is named for the scientist who discovered it. Friedrich Lewy was a 25-year-old Jewish researcher two years out of medical school when in 1912 he published the landmark paper describing oddly-shaped proteins that he had found while autopsying the brains of patients with Paralysis agitans. Researchers later named the paralysis Parkinson’s disease and the proteins Lewy bodies. Lewy was relieved of his professorship in Berlin in 1933 after the rise of the Nazis. He emigrated to the U.S., changed his name to Frederic Lewey, and shifted his research away from cognitive disease.

Meanwhile, following the death of Alois Alzheimer in 1915, his leading proteges became true believers in eugenics theory. They argued that Alzheimer’s disease was caused by “hereditary degeneration” which could only be eliminated by controlling inferior breeds of people. One ardent promoter of Alzheimer’s work became Hitler’s commissar of racial hygiene.

And things got no better post-Hitler. In his book The Problem of Alzheimer’s, Jason Karlawish laments that after World War II American psychiatry showed little interest in the biological causes of mental illnesses. Instead the profession rushed to embrace Freudian theories of neurosis (i.e., anxiety and depression), and to create lucrative practices around the “talking cure” of psychotherapy, which was of no help to people with dementia.

Karlawish sums it up nicely:

Throughout the world for much of the twentieth century, the diagnosis and treatment of dementia in an older adult essentially fell between the two professions who cared about the brain: neurology and psychiatry. It was neglected.

Land of Linkin’

In L.A., “what fills my heart in the face of destruction are the thousands of eager helpers”

A provocative reflection on Jimmy Carter’s empathy problem

Not one but two eulogies read at Carter's funeral were written by men who themselves had died

Norway is going to rule us all someday!! (and we’ll love it)

In local news, the only Evanston man to serve as Vice President was also the only VP to write a hit song

Soup club regulars tell me I outdid myself with this black eyed pea Ethiopian stew

Wisely, the editors of the New Yorker chose the early years of SNL for its lengthy excerpt from the new Lorne Michaels book

“A Kiss To Build a Dream On” was taken from Satchmo’s 1968 BBC concert that was remastered and released in 2024 (by the way, it’s “Lewissssss” not “Lewy” Armstrong)

Thank you’s

TDP’s Bookshop links benefit the Robert H. Levine Foundation for Lewy Body Dementia Research.

Diane and I wrote and published a number of books on American history which you can buy directly from us.

Yes, you can forward this newsletter — I encourage it! If someone forwarded The Diane Project to you, consider subscribing. It’s free, with newsletters once or twice a month.

When you subscribe, I’ll send you What Every New Cognitive Caregiver Needs To Do. It’s the guide I wish I had when I was starting on my journey.

Thanks for reading,

Aaron

Dear Aaron and Diane,

You two have been a true team all along, and even when this rude Lewy entered your lives, you are still making it work. I totally admire the way you have lived, and now honestly and courageously sharing the details for us. I think you are helping many people. As for us, I have macular degeneration which is getting worse. We see a Retina Specialist tomorrow. Yesterday I said to Leroy "I'd rather be dead than to lose my vision." He said, "Don't say that." I said, Will you let me get a guide dog?" He said, "I'll be your guide." A dog can't make coffee." I'm sure we'll make it; thanks for showing us it can be done. Give Diane a hug for me. Love to you both. June

Thank you for living and taking care of my aunt Diane, she is lucky to have you.

Jane