This is Kansas Day (Part 3)

Grief and the manly caregiver

Final part of an essay on my wife’s midlife reinvention. Here’s Part 1. And here’s Part 2. Rather listen than read? Click the audio widget to hear me reading the “Kansas Day” series, all three parts.

***

It’s a blustery early spring day in Chicago but as soon as I click on the video, I feel warmer. I’m transported to that summer night in 2003 outside a charming old house in Topeka. The house belongs to Ron and Annette Thornburgh, one of the more prominent couples in the capital city of Kansas.

There are people standing in clusters chatting pleasantly on the Thornburghs’ front porch. The video footage is unsteady. I’m on the lawn trying to figure out my new camcorder, which has more buttons than a Shakespearean costume. As I take a few shaky establishing shots, I hear a woman’s laugh above the chatter and think: I know that laugh.

Inside the house, people are holding drinks and talking in groups. Moving among them is a tall, friendly lady in a black dress whose badge identifies her as Marion Cott, director of the Kansas Humanities Council. These are her people — donors, board members, allies in government. Originally from Iowa, Marion has spent 30 years building the KHC into a force for good in her adopted state, promoting civic values and lifelong learning. It awards dozens of grants a year in support of small-town and rural-friendly projects: oral history, film festivals, educational talks.

KHC’s big initiative in 2003 was a traveling exhibit titled “Produce for Victory: Posters on the American Home Front.” But tonight is about a much more ambitious project that’s launching next year. And like The Diane Project, it has my wife at the center.

Since the 1980s the KHC has sponsored the Kansas portion of the Great Plains Chautauqua, a five-state road show that mixes enlightenment with entertainment. A traveling band of scholars give talks during the day and perform as historical characters — Sacagawea, Teddy Roosevelt, etc. — at night under a big top. To mark the 150th anniversary of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 2004, Marion wanted KHC to have its own chautauqua. This one would shine a light on the often-overlooked role that Kansas played in the leadup to the Civil War (as I described in Part 2).

Diane applied for the part of Clarina Nichols, and despite her lack of scholarly background or acting experience, Marion picked her. And tonight she’s starring in a VIP preview of the 2004 Bleeding Kansas Chautauqua. We’re doing it at the home of the Thornburghs because Annette is on Marion’s board and is married to the Kansas Secretary of State. (Ron was elected to four consecutive terms as a moderate Republican, back when those creatures roamed the earth.)

You would never know this is Diane’s performance debut. There she is on the front porch, minutes before showtime, just yakking with folks like it’s a charity event for Saint Francis Hospital in Evanston, where she was director of public relations in the ’80s. All of her familiar qualities are on display: her smile, attentiveness and good humor — but what people probably noticed is the incredible 19th-century period costume she has on. The wig was designed with the ringlets that Clarina wore in her hair. The dress, inspired by New England styles of the day, was made for her by a Lawrence quilter and dressmaker.

Once everyone goes inside and is seated, Diane is introduced by Marion, delivers a half-hour monologue crafted from Clarina’s own writings, answers a few questions as Mrs. Nichols, then takes off her wig and answers questions as Diane. This cutdown is 15 minutes long and worth a watch.

The Bleeding Kansas Chautauqua kicked off in Junction City the first week of June, 2004. Most of our family attended that one. Next was dusty Colby, way out west, then historic Fort Scott in the state’s southeast corner. The finale, which played to the biggest crowds, took place in Lawrence’s South Park, near the University of Kansas.

Each site was treated to five nights of performances. College professors Fred Krebs and Richard Johnson debated amicably as Lincoln and Douglas. David Rice Atchison and John Brown (aka Dave Dickerson and David Matheny) each got his own night. Charles Everett Pace breathed fire into Frederick Douglass’s Fourth of July address.

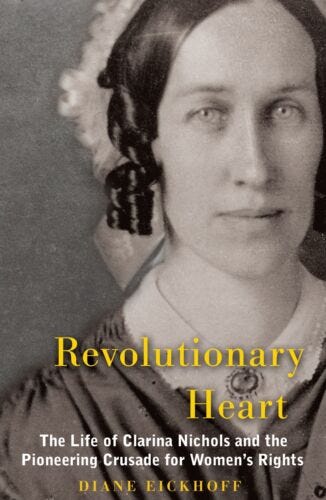

Diane’s performance in Lawrence was memorable, and not just because the tent was filled to capacity. In the audience was Janice Parker, a direct descendant of Clarina Nichols, whose grandmother Diane had interviewed for her book (and who told Diane that her name was Clah-RIH-nah, not Clah-REE-nah). Janice brought a very special heirloom with her — the brooch that Clarina wore in the 1843 picture that I featured on the cover of Revolutionary Heart. Diane wore it for her performance that night.

The book came out in 2007. With support from the KHC, Diane kept doing her one-woman show. The demand seemed endless. It was not easy for Diane to put on a period outfit, perform a script from memory, and take questions from audience members she couldn’t see because of her poor vision. I’ll bet she did it at least a hundred times.

Had Marion Cott not retired and the KHC put an end to the Living History program, Diane would probably be performing in that wig and dress until her diagnosis. (Well, she probably wouldn’t have made it quite that far, but that’s a story for another day.)

Instead, armed with her new master’s degree and the tools of historiography, she went into the history business. The humanities councils in Missouri and Kansas wanted relevant talks on history. The pay was enough and we could sell books afterwards. Over the next 15 years we covered most every highway in two states.

Diane gave different talks over the years, but they always had something to do with women’s struggle for basic rights or the roles of women in the Civil War era. These topics were not only novel and interesting to her audiences, but gave Diane an excuse to work Clarina Nichols into every single talk.

After I left the newspaper in 2012 we became a writing-lecturing team, leading Osher Institute classes, addressing Civil War Roundtables across the Midwest, and appearing on C-SPAN. We published books on local history and women in the Civil War, and were working on our most ambitious book project when it all came to a sudden stop in 2020.

It was Lewy, not Covid, that put us out of business. Diane’s diagnosis forced us to drop everything and pivot to downsizing and moving. We never gave another talk and we shelved our work-in-progress. By the time we arrived in Evanston in 2022, Diane had forgotten that she was the one who had given Clarina Nichols her place in history.

But it turns out there was someone in Kansas who hadn’t forgotten Diane.

***

I received this email out of the blue last November:

“Hello, my name is Phyllis Pease and I am the artist that is working on the Kansas suffragist memorial. Clarina is front and center of my painting and in my sketch I have her wearing the memorial brooch. Would you happen to have a better photo of it.”

Having no idea what this “suffragist memorial” was, I searched online, and learned that it was a project of the Kansas League of Women Voters, at whose convention Diane once spoke. The legislature had passed a bill allowing for a “memorial” — actually an 8-by-19-foot mural — to be installed in the Kansas Statehouse in Topeka to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. Kansas women had actually gotten full suffrage in 1912, eight years before the passage of the 19th Amendment.

The mural would be painted by Phyllis Garibay-Coon and would be on permanent display on the first floor of the Statehouse, on the same wing, two floors down from one of the most illustrious murals in America: John Steuart Curry’s “Tragic Prelude,” famous for its 20-foot-high, hair-on-fire portrait of the abolitionist John Brown.

I could only find an early sketch of the mural, titled “Rebel Women,” but there was Clarina front and center, holding a lamp, leading a legion of suffragists whose work, as I knew from Diane’s talks, had spanned six decades of Kansas history. It had the feel of a traditional, overstuffed historical mural with a bit of comic-book flair. But it also had a special quality. It seemed so … joyous. Even in rough-draft form, it made my heart leap.

Tears welling up, I sent Phyllis the photo I posted above, the one of Diane wearing Clarina’s brooch. Phyllis wrote back:

“Oh my gosh Aaron this is a great picture! Thank you so much for sharing this with me. I’ve read all of Revolutionary Heart. I think Clarina is an amazing woman, and if I could go back in time that’s who I’d want to meet.”

Now I wanted to know all about this mural and the woman bringing it to life. So I got Phyllis on Zoom with Diane. Here’s an edited version of our interview. We started off talking about surnames.

Why did you introduce yourself to me as Phyllis Pease when you’re signing your painting as Phyllis Garibay-Coon?

I got divorced several years ago, and I haven’t officially changed my name back to my maiden name. Because it was in the Statehouse, and my parents are Kansans and [my ex’s] family is from Nebraska, it just kind of prompted me to like, “I want to honor my families.” I wanted to honor both my parents because they went through a lot to be married.

It was a mixed marriage. My mom’s Mexican. She emigrated when she was a child from Michoacán. [Her family] ended up in Kingman County. They both came from farm families. He’s German-Scotch-Irish. They moved from Illinois. That’s the other thing. It was a mixed marriage because my mom was Catholic but my dad was not.

My mother passed away several years ago but my dad’s 100. He’s still alive and kicking. Really a wonderful story of these two people that met and got married and had 10 kids and farmed. My mom was the fire, my dad’s quiet. Every day he asks my sisters, “How’s the painting going? What’s going on? So excited for Wednesday!” That’s why I changed [my name]. I'll start signing my art that way, too.

(I then told Phyllis that my wife grew up on a farm as well, near Wykoff, Minnesota. “She’s an Eickhoff from Wykoff!” I said, which got a laugh from both Diane and Phyllis.)

How did this project come about? How was it commissioned? And how were you commissioned?

The League of Women Voters and the AAUW. It all goes through the State. But it’s all privately funded. The League of Women Voters made the proposal, and they were granted the space. They put the net out for artists. They wanted Kansas artists.

I've done a big [MLK] painting at the Zoo here, Sunset Zoo, and I have a painting [of Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez] at Kansas State University. I love to paint big and it’s kind of nostalgic-inspired.

I had not heard about this project. I don’t know how they advertised it, but not well enough because they didn’t get enough input, so they extended the deadline. A woman came into our small business — [my daughter and I] have a little bakery and a restaurant — and said, “Hey, your mom should do this project.” So I applied, and they narrowed it down to five artists. And then each artist had to present their idea.

They gave us a list of 20 [suffragist] women, and there was a snippet on each one of them. Of course, Clarina is on the first page. So I read Revolutionary Heart. I mean, after I started reading about Clarina, I said, “Oh, she’s a freaking superhero.” She is the one in front and center.

There was a guy who teaches at KU and he’s like a heavy hitter and I’m like, “I can’t believe I’m up against this dude.” But he’s a dude, and the League of Women Voters were like, “You know, we really want a woman to paint this painting.”

I got a peek at some of the other people’s ideas. They kind of focused on nationwide suffragists, a general story as opposed to Kansas women.

Ohhhh, big mistake!

Yeah. So I did the research.

The Preservation Committee chose me to be the artist, with changes. They didn’t have a problem with my composition or what I had in it. I have Lawrence burning. I had the territorial capital [Lecompton], the border wars, because Clarina’s sons fought in the border wars. So that was great. And I said, “OK.” I was a graphic designer. That’s what I graduated as and worked as in a firm. So I understand design-by-committee and I expected there to be some changes. We worked together to choose the women, but they always wanted Clarina to be be featured in the project.

There are at least three dozen women in this painting. Is there going to be an explainer?

There’s a plaque that will sit underneath the painting and there will be a key that will number left to right. Each of the suffragists will have their name, what town they were from. And what’s cool is, these are people that existed in time.

They have hundreds of kids who come through there every day. And their teachers. The tour guides are so excited. The tour guides — I was just there for [a few] hours — but every one of them would stop and say, “Oh, my gosh, I’m so excited to now come down this hall and talk about these women!” They were already rearranging their tours in their heads. And one of them said, “I’m going to have to cut something out — I know exactly what I’m going to cut out,” so she can make it to that hallway for the tour.

“Rebel Women” was unveiled by Governor Laura Kelly on Kansas Day, January 29, 2025. Phyllis’ sisters were on hand, but not her 100-year-old father. He had passed the day before.

I had yet to see the finished mural, so I began hunting for images online. One search led me to the website of Kansas Public Radio’s “KPR Presents,” hosted by Kaye McIntyre. When Revolutionary Heart came out, Kaye had dedicated an episode to Clarina’s story and had interviewed Diane. Ahead of the Kansas Day ceremony, Kay interviewed Phyllis and took this photograph that accompanied the podcast of the show:

There was the brooch, and something else that hadn’t been in earlier photos: the knitting needles! This was Diane’s favorite detail from the 1859 free-state constitutional convention. Clarina attended every day and sat in the press section, and she brought her knitting. A New York Times reporter sitting next to her wrote this line that Diane loved to quote: “Mrs. Nichols sits at the reporters’ table every day, some of the time plying her needle, some of the time her pen.” Imagine sitting in a smoke-filled room of shouting Democrats and Republicans and then, during a lull in the action, hearing the click-click of needles. Diane loved that detail — and so did Phyllis.

The moment I saw this picture, I felt overwhelmed. As I listened to the podcast, I just stared at that picture on my screen and sobbed helplessly. Diane held my hand tightly and silently.

***

I know I have put forward a cheerful and somewhat brave face during this season of The Diane Project. It’s not an act. Well, it’s not an act any more than Diane performing as Clarina Nichols — a woman with whom she deeply identified, despite the century and a half between them — was an act. This is who I am now. I’m a manly caregiver.

Women and men, in my experience, have distinct ways of projecting strength and assurance. Diane and I complemented each other. At times I put a little steel in her spine; other times, she tamed this bull in the china shop. I’m perfectly comfortable taking my wife to church every week and parking her wheelchair in the front row. I’ve gotten pretty good at talking about Diane’s dementia and making her care sound as natural as any other family activity.

I’m not a hero any more than any other human who was conscripted into the army of caregivers. Several dads I know have kids who were born with special needs. We can relate to each other. I would like to see more men lean into caregiving roles. They can handle it better than they think. Also, I believe that having more men take on the responsibilities of care instead of looking for the nearest available woman would be a huge cultural shift for the good. We need one of those right now.

Having said all that, I must admit that my description of life as a manly caregiver has not been complete. We must now talk about the hardest part of the job, which is the emotional part, specifically grief.

It’s been three months since I first set eyes on Phyllis Garibay-Coon’s inspiring mural, and it still reduces me to tears. I can’t look at it or even think about it without watering up. This isn’t the “so proud of you!” trickle tear that rolls down the cheek when your loved one is recognized for an achievement, although it did make me mighty proud to see Clarina front and center, leading the avengers.

No, I’m crying because I’m grieving. And I’ve been grieving a long time. Watching Diane go through all the changes the first two years after her diagnosis was hard. In real time I lost not only our partnership but, eventually, her companionship as well.

Elissa Strauss, whom I interviewed in my first issue, interviewed me for CNN.com about caregiver grief. The takeaway of the story is that caregivers often have no choice but to deal with emotions while, at the same time, doing their best to care for a loved one. That described me to a T, but until I read Elissa’s story I hadn’t really looked at it that way.

So then I began thinking more about the role of grief in my caregiving journey. As you’ve followed me on The Diane Project, you’ve seen how I relish the challenge of caregiving. It gives me a sense of accomplishment to do right by my baby. But if I think back over the past three years, there have been many moments when I’ve been alone and heard a sad song on the radio, or found myself awake in the wee small hours, and surrendered to my sorrow.

Then I looked back at my story about soup club and realized, oh hey, there I am coping with my grief in very practical ways. I’m turning off the news to avoid piling on the pain. I’m making new friends and rebuilding my social network to regain some of the emotional support I lost when Diane got sick.

The next story was “This is the kiss test,” where I quoted caregiving coach Pat Snyder telling me that after this journey, “you’re going to be able to love more deeply and have much more compassion, because you had to.” But we didn’t talk about grief, probably because I didn’t want to.

With the Clarina mural, though, the walls of resistance came crashing down. That led to this three-part “Kansas Day” series on my wife’s midlife reinvention. I knew I couldn’t write about my grief without giving you a sense of all that I lost. By now I hope you understand why I said, in the opening lines of The Diane Project, that she is the woman to whom I owe everything. And why I am glad to be her full-time caregiver for as long as it takes to give her a safe and gentle landing in the next dimension.

My friend Ric Hudgens wrote a good reflection recently on grief and grievance. He notes that men who act out in anger are usually avoiding their own pain. By confronting pain we experience grief, which is the necessary antidote to the poison of grievance. “We are all capable of addiction to grievance,” Ric writes. “We must remind ourselves regularly that loss is constant and universal.”

He’s right. I could just as easily have avoided the pain and spent those years in a state of anger over the unfairness and cruelty of cognitive illness. I know some male caregivers who have anger issues and all can say is: There but for fortune go I.

It certainly worked to my benefit that this wasn’t my first rodeo. My caregiving journey with Diane spans the course of a long and fruitful marriage. Indeed, that through-line of mutual care is one reason why our marriage has been long and fruitful.

For how much longer, though?

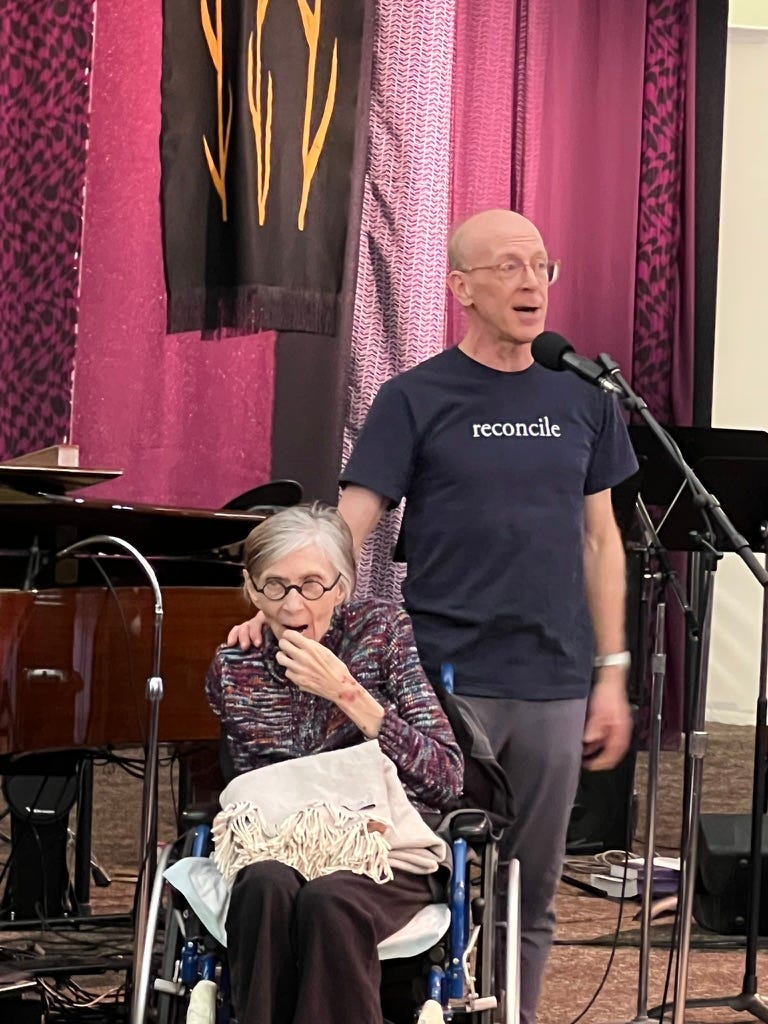

On Palm Sunday I told our faith community that we are transitioning Diane to hospice care. I told them that not much was changing, that everything will stay home-based, but now I’m getting some extra (and much-needed) help.

The truth, however, is that things are changing. I still go in for the kiss test, but her kiss is getting weaker. I look in those tired eyes and hold that hand with its still-strong grip. She’s hanging on, but I can feel that still-strong grip loosening. I think this will end beautifully for her — but I’m going to be a wreck.

So I’ve decided to take a break from The Diane Project. We’ll call this the Season 1 finale. I plan to return with Season 2 in the fall. In the next four weeks I’m going to run a marathon. I’m going to celebrate my 60th birthday — and our 30th wedding anniversary — and I’m going to Kansas for a grandson’s high school graduation. And I will visit the Statehouse in Topeka to see “Rebel Women” in person. I will bring tissues.

If there are any major developments on the home front, of course I will pass them along.

Endnotes

Here’s Part 1 and here’s Part 2 of “This Is Kansas Day.”

My reflections on grief were aided by “The Curse of Grievance” by Ric Hudgens on his Substack, The Brink. Ric is a retired pastor who lives in our neighborhood. He was also the best man at our wedding and a dear friend going back to small-group days in our faith community. I’m publishing this today because it is Ric’s 70th birthday.

Elissa Strauss’ excellent book When You Care is now in paperback. I have a number of recommended titles on my Bookshop page.

While researching this story I learned that Charles Everett Pace had passed. He was my (and Diane’s) favorite chautauqua performer. I also saw him in 2009 conversing with Crosby Kemper as though he were Langston Hughes in the flesh. The video I posted of Charles performing as Frederick Douglass is one of my most-watched YouTubes.

Tours of the Kansas Statehouse are held pretty much every hour, year-round. Totally worth your time.

During the break I will send out a special thank-you gift to those of you who subscribe to our Substack. Look for that in your email. If you aren’t a subscriber yet, please hit the button below.

Thank you’s

Thank you for taking a moment to answer the one-question poll above so I can get a better idea of who’s out there.

Thanks for shopping TDP’s Bookshop links, which benefit the Robert H. Levine Foundation for Lewy Body Dementia Research. Bookshop now features ebooks.

Thanks for checking out the history titles that Diane and I wrote and published.

Thank you for sharing this newsletter with others.

If someone forwarded The Diane Project to you, consider subscribing. When you do, I’ll send you What Every New Cognitive Caregiver Needs To Do. It’s the guide I wish I had when I was starting on my journey.

Thanks for leaving your thoughts and questions in the Comment area.

Above all, thank you for reading.

Take care,

Aaron

I am new to your blog; found your blog before Zi really KNEW what was happening to my life partner of 50 years. Recently got confirmation of Alzheimer's diagnosis. We married in med school & have had a lovely life of family, friends & travel. Prior to his retirement,

I watched his behavior and speech change & I even kept notes to see if I could identify a trigger. Was it a medication, a brain tumor, long COVID? Then I wondered the worst -Lewey body, alzheimers, or the Bruce Willis dementia? Because he was a physician, it was hard to get him to the doctor for evaluation. And harder to push them to look further and deeper into what I saw.

He's now on the newest infusion treatment for Alzheimer's. Say a prayer.

Do I know you're taking a break--but before you sign off , I just wanted you to know that the BEST tool for "dealing" was your post about separating the disease from the person & giving it a name. This has been so helpful in keeping my frustration in check & compartmentalizing my feelings about his behavior. Thank you, thank you!! And God-speed in your journey to find peace and hopefully joy in YOUR LIFE! You only get one; so glad you're embracing some "all about YOU" activities!!

This is fantastic. Thank you!!